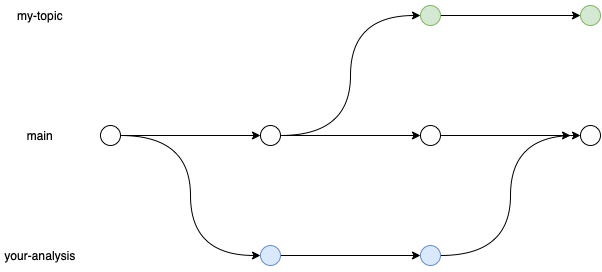

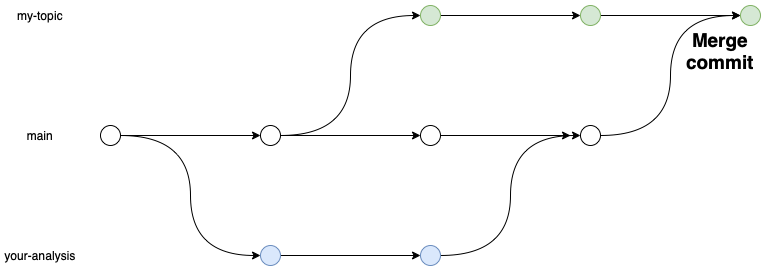

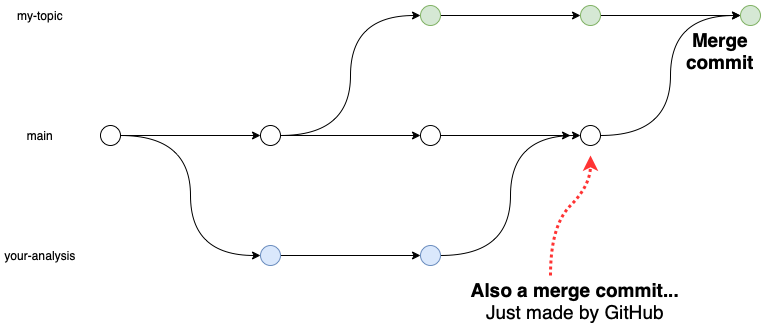

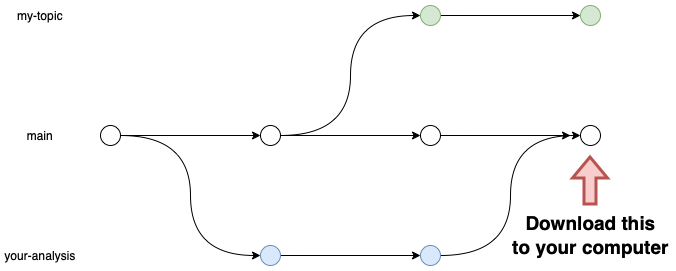

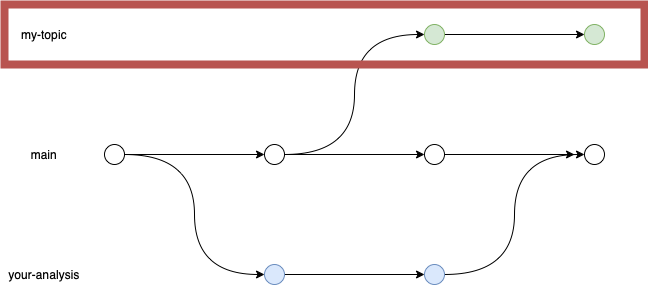

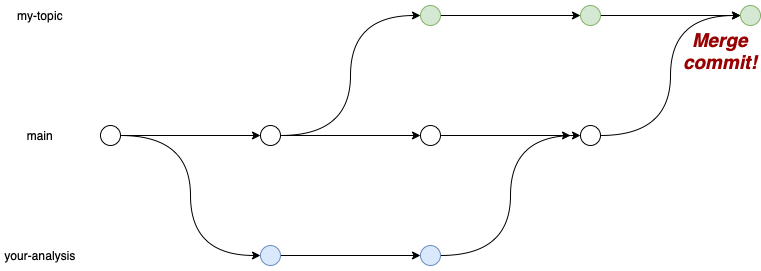

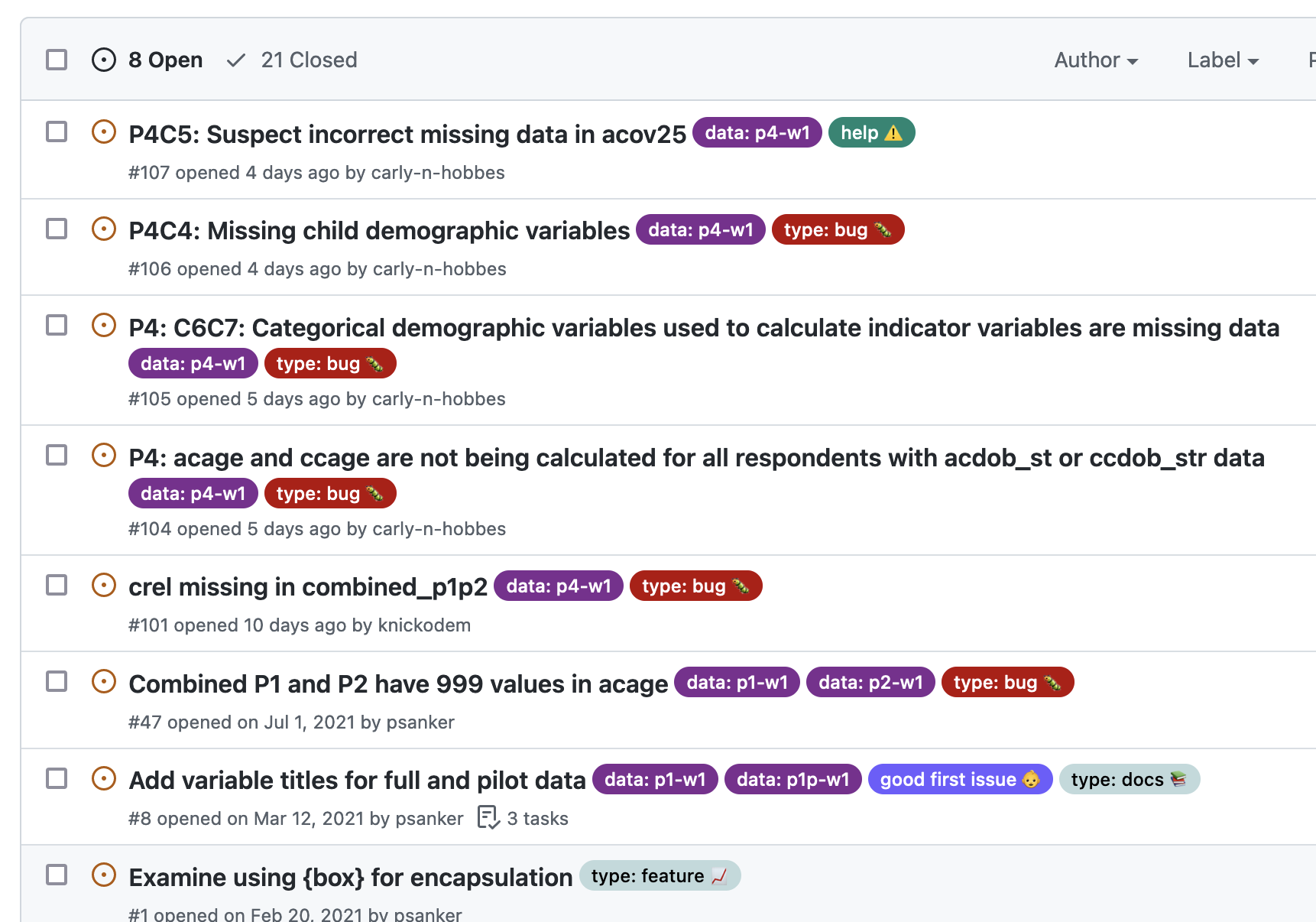

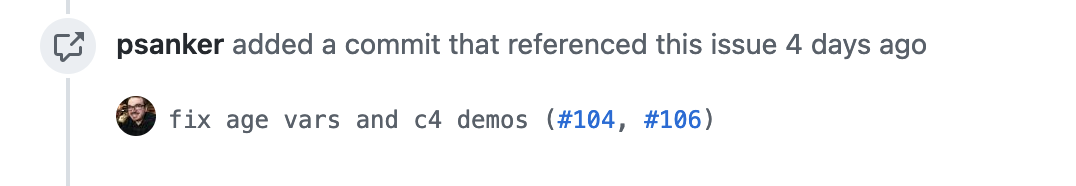

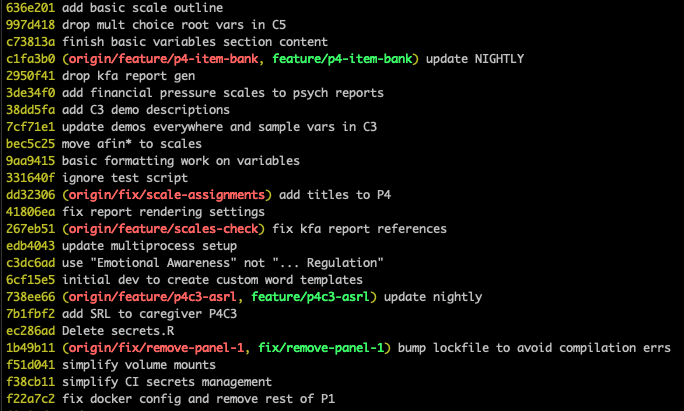

class: center, inverse, middle, title-slide # Let's Write a Paper! ## Part III - Collaboration & Workflow Styles ### Patrick Anker .ties-footer[  ] --- class: middle, center ## Before we begin... If you'd like to download any of the materials for this presentation, check out **>> [the workshop's website](index.html) <<** ### 🚀 --- # Agenda .pull-left[ So far, we have covered - Introduction to GitHub & git - How to create repos - How to manage changes with commits and branches - How get changes from and send changes to Github with `git pull` and `git push` ] .pull-right[ Today, I want to cover: 1. How to merge work from other branches 1. Issue tracking 1. Different collaboration styles & commit conventions ] --- class: middle, center, inverse <script src="https://kit.fontawesome.com/8dd08732ee.js" crossorigin="anonymous"></script> # Merging ## .yellow[<i class="fa fa-code-pull-request"></i>] --- # Merging Collaboration is only useful if we are able to combine our work on our different branches. We achieve this using a git **merge** .definition[ ## Merge A mechanism that takes two (or more) histories and reconciles the differences in a line-wise fashion. ] We've already used a mechanism that implements a merge before, and that's the **Pull Request** feature on Github! However, Pull Requests are really some nice window dressing around merges, and sometimes it's useful to merge work _outside_ of the context of a Pull Request. --- # Merging Consider this example: .pull-left[ I'm working on a particular section of a report, and things are going swimmingly. However, I noticed that something in your analysis would be very nice to include in my report, but your analysis work was already merged into `main` via a Pull Request. How can I get your analysis work into my branch so I can make the changes in my report prior to creating a PR? ] .pull-right[  ] --- # Merging .center[] .center[**.red[with a merge commit!]**] --- # Merging .center[] .center[Github also makes a merge commit once a Pull Request is merged.] --- # Merging To perform this kind of merge, all you need to do is follow these steps: .pull-left.font12[ Action | Example :------|:-------- 1. Switch to the branch you'd like to merge in | `git checkout main` ] .pull-right[  ] --- # Merging To perform this kind of merge, all you need to do is follow these steps: .pull-left.font12[ Action | Example :------|:-------- 1. Switch to the branch you'd like to merge in | `git checkout main` 2. Download changes to your computer | `git pull` ] .pull-right[  ] --- # Merging To perform this kind of merge, all you need to do is follow these steps: .pull-left.font12[ Action | Example :------|:-------- 1. Switch to the branch you'd like to merge in | `git checkout main` 2. Download changes to your computer | `git pull` 3. Switch back to your branch | `git checkout -` ] .pull-right[  ] .footnote.font12[ The `-` is a shortcut for "previous branch". It's just like `cd -` from moving around th Terminal! ] --- # Merging To perform this kind of merge, all you need to do is follow these steps: .pull-left.font12[ Action | Example :------|:-------- 1. Switch to the branch you'd like to merge in | `git checkout main` 2. Download changes to your computer | `git pull` 3. Switch back to your branch | `git checkout -` 4. Merge in the changes! | `git merge main` ] .pull-right[  ] --- # Merging These steps are the same for command line and for SourceTree: 1. Switch to the branch you'd like to merge in 1. Download changes to your computer, if they don't already exist 1. Switch back to your branch 1. Merge in the changes .pull-left[ ### Command Line .font12[ 1. `git checkout <target branch>` 1. `git pull` 1. `git checkout -` 1. `git merge <target branch>` ] .font10[ Note: After running `git merge` you may be thrown into an editor called "vim". Just remember this keystroke sequence and all will be well: `:wq<Enter>` ] ] .pull-right.font12[ ### SourceTree 1. Double-click on the target branch you'd like to merge in 1. Click "Pull" 1. Double-click on the branch you're working on 1. Click "Merge" and then select the commit that has the target branch's name tagged to it ] ??? - Pause for questions before moving on --- class: middle # The Golden Rule of Merging > .red[Merge] to bring **someone else's** work **into your** branch; .red[Pull Request] to send **your** work **into someone else's** branch Adhering to this rule will handle much of complexity and confusion that git can cause. This also creates a great social contract for you and your collaborators: adapt from others to create something new for yourself, ask permission to give back to others. --- # A Tip ### Getting A Single File From Another Branch Suppose that your collaborator has a file change that you want to adopt, but you don't necessarily want to merge in their entire branch. How do you get it? .pull-left.font12[ **As far as I know, this is something you can only do with the command line interface**. You must use the command: .font10[ ```sh git checkout <branch name> -- path/to/file.txt ``` ] An important thing to know is that this operation .red[**overwrites**] your work on that file, avoiding a merge conflict. If you want to merge your work, it would be better to use a merge. ] .pull-right.font10[ ```sh git checkout topic -- config/mapping.csv ``` ] ??? - Moving onto merge conflicts after this, so ask for any questions about merging in general --- class: middle, center, inverse # Merge Conflicts ## .yellow[<i class="fa fa-code-pull-request"></i>] 🙅 😫 --- # Merge Conflicts Even with the best workflow, you will encounter merge conflicts. **And that is okay!** Embrace the merge conflicts. Accept them. .center[ ## .red[<i class="fa fa-spa"></i>] ] In all seriousness, it is expected that you will encounter merge conflicts if you and your collaborator happen to edit **the same line**. .pull-left[ Unlike Box, however, git will tell you where the conflicts arise and guide you on how to resolve them. When you merge something that generates a conflict, you will see this: ] .pull-right[ ``` >>>>>>> your-current-branch text that was in your branch ... ======= text that was in the other branch ... <<<<<<< branch-youre-merging-in ``` ] --- # Merge Conflicts .pull-left[ The merge conflict chunks come in three parts: 1. `>>>>>>> [where you are, often "HEAD"]` followed by the content in your branch 1. `=======` - a partition between the two content areas 1. The content from the branch/commit you're merging in followed by `<<<<<<< [what you're merging in]` ] .pull-right[ ``` *>>>>>>> your-current-branch text that was in your branch ... *======= text that was in the other branch ... *<<<<<<< branch-youre-merging-in ``` ] --- # Merge Conflicts .pull-left[ All you need to do is: 1. Pick the content you want to keep between the two (could be a combination of both!) 1. **Delete** the lines with `<<<<<<<`, `>>>>>>>`, and `=======`. 1. Commit the changes! ] .pull-right[ ``` >>>>>>> your-current-branch *text that was in your branch *... ======= *text that was in the other branch *... <<<<<<< branch-youre-merging-in ``` ] --- class: middle, center, inverse # Issues ## 🗒 --- # Issues .pull-left[ Issues are a part of Github's project management suite, like tasks on Asana. Each issue has its own number<sup>1</sup> that can be referenced with a pound sign (e.g. **\#5**). ] .pull-right[  ] .footnote[ [1]: You can refer to Pull Requests using this scheme, too! Pull Requests are just fancy issues. ] --- # Issues .pull-left[ If you want to mark a commit as referncing another issue, just put the commit number in the commit message, e.g. `fix bug that would duplicate analysis (#20)` ] .pull-right[  ] --- # Why use issues when we have Asana? This is a practical question that I've tinkered with while working at TIES, and my conclusion for when to use Asana vs. Github issues is as follows: 1. Use Asana for larger project milestones and roadmaps 1. Use Github issues to track bugs / unexpected behavior While there are tools to integrate Asana and Github issues, they aren't perfect for both situations. Keeping this division has so far been fairly successful on the Data Team. --- class: middle, center, inverse # Collaboration Styles ## 👩💻 👨💻 --- # Collaborating There are three main collaboration styles with git: .pull-left.font12[ 1. **Shared repository / central backup** 1. The most common use style 1. Useful for private projects and projects with a few collaborators 1. Project leaders need to manage access permissions 1. **Forking** 1. Popular in open source software 1. Not great for private repositories / projects 1. **Peer-to-peer** 1. Primarily used by UNIX wizards and folks who don't trust central code repos 1. Hard to know which repo is the "live" repo ] .pull-right[    ] --- # Collaborating .pull-left[ **In most cases**, we should be using the "Shared Repository" model for our projects since we mostly want **privacy** and **security**. By default, **all _private_ Github** repos are **hidden** on the NYU Global TIES Github org. You will need to add people to have access (I can help with that). ] .pull-right[  ] --- # Commit Messages _What makes a good commit message?_ Commit messages are the core description of changes in our git log. You should be able to understand what happened in your repo just by glancing at the log. Remember: this log isn't just for others; this is also for you a couple months or years down the line. These are some suggestions from the wild: .pull-left.font12[ 1. Use imperative case e.g. "remove routine that was crashing OSF lookup" 1. Be informative and clear with your messages: don't do "update script.do", do "fixed linear regression syntax" Totally optional, but I highly recommend the [**Conventional Commits**](https://www.conventionalcommits.org/en/v1.0.0-beta.2/) format as some other tools are out there that can help generate changelogs and other documentation automatically from your commit messages. ] .pull-right[  ] --- class: middle, center, inverse # Questions?